Exit, pursued by a bear

- William Shakespeare, The Winter’s Tale

We are obsessed with just a couple of themes in energy markets today. Front and center is the energy crisis in Europe, particularly with respect to natural gas. We are simply astounded at how quickly the situation has deteriorated and are fearful for the damage that will likely be inflicted on the continent in the upcoming winter.

Europe is dangerously dependent on natural gas imports from foreign sources. Over the last year, Russia has gradually but deliberately curbed natural gas exports to Europe. Elevated European LNG imports have offset to a degree, and at tremendous cost, but the most recent drop in Russia volumes raises the real prospect of Europe simply running out of gas this winter. The marked disruption in natural gas flows since the Russian invasion of Ukraine has all but ensured an economic recession and now poses the risk of inflicting human pain and suffering this winter.

Europe is out of options to further displace Russian gas this year. There is a nonzero probability of widespread humanitarian catastrophe in the 2022/2023 winter - largely contingent on what Russia decides to do with its gas over the next few months.

Overview

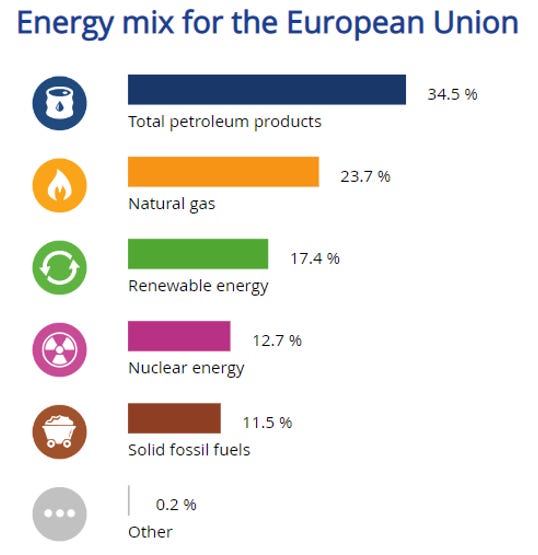

Natural gas comprises just under a quarter of the total energy mix in the European Union. At the high end, Italy and the Netherlands rely on natural gas for about 40% of total energy. At the low end, the Scandinavian EU states use natural gas for only 5% of total energy needs.

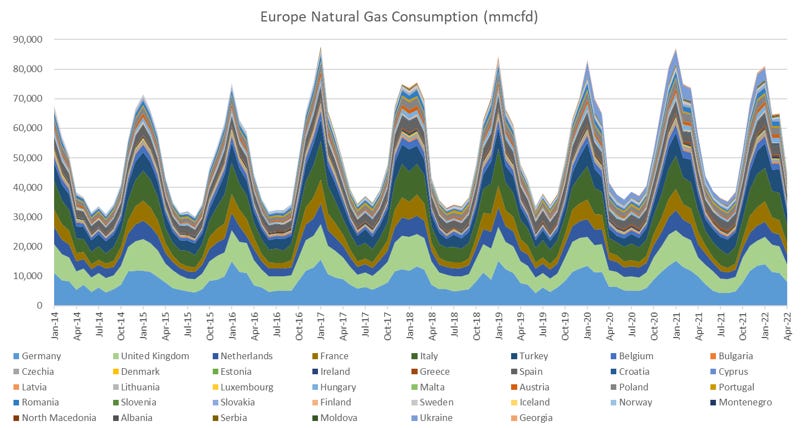

Europe consumes ~35 bcfd gas during seasonal low demand periods in the summer and upwards of 80 bcfd of natural gas during the winter.

Residential/commercial demand comprises 57% of the total, with industrial demand making up 33%.

Depending on the time of year, the region consumes anywhere between 35 and 80 bcfd but produces only 20 bcfd. Care to guess how many countries in Europe produce over 1 bcfd?

Answer: 3 - Norway, UK, and the Netherlands. Of those, only Norway produces more than 4 bcfd.

Excluding Norway, the persistent decline in indigenous production is glaring, and we suspect irreversible. We expect the trend to continue in the near term.

With consumption well in excess of production, a simple mass balance dictates that Europe must import natural gas to make up the deficit. The region imports gas via pipeline and LNG terminals. We walk through each medium below.

Pipelines

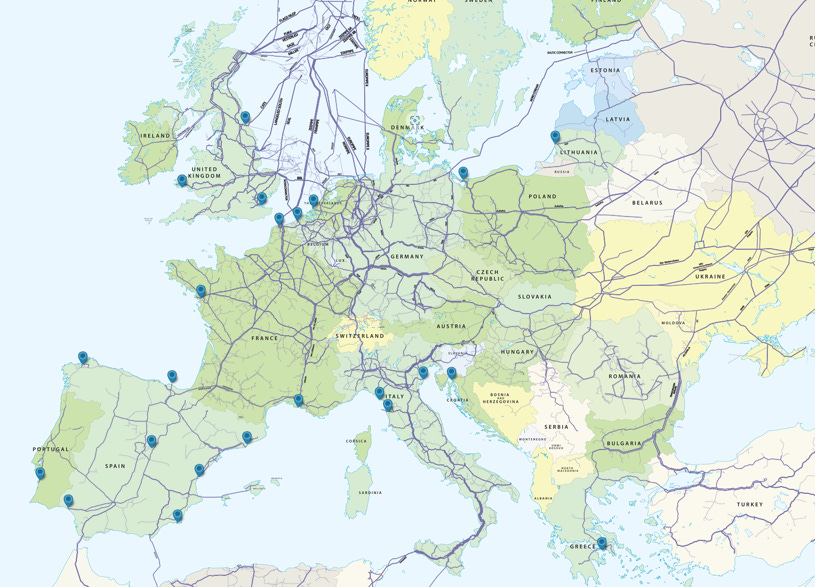

The Eurozone (incl UK) has built infrastructure tying itself to a handful of regional gas exporters.

Southern Europe & Iberian peninsula: access North African natural gas production from Algeria and Libya

Southeastern Europe: access Azeri gas through Turkey

Northwestern Europe: access Norwegian production through a number of pipes crossing the North Sea

All of Europe: intricately connected to Russian gas through four primary pipeline networks

We show herein that Europe has limited ability to source pipeline gas from any supplier that is not Russia.

Russian pipeline systems in red, other suppliers in blue

Starting down south, Algeria and Libya supply gas to Europe via four pipelines landing at terminals in Spain and Sicily.

Flows on the lines this year have been relatively steady, though Spain is still feeling the pinch from Algeria’s decision to stop shipping down the Maghreb-Europe (MEG) pipeline in 2021 after a dispute with Morocco regarding the sovereignty of Western Sahara. After shutting down the MEG line, Algeria committed to diverting all supply to Spain into the Medgaz pipeline, but it’s plain to see that today’s Medgaz flows fall short of last year’s Medgaz + MEG flows.

Across North Africa, volumes in the operational lines today are below design capacity, suggesting upstream deliverability constraints are prohibiting the ramp up production into Europe. European buyers would take more gas, but upstream producers cannot ship more. No incremental volumes coming from North Africa.

New to the scene in 2021 was the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) transporting gas from Azerbaijan into Europe transiting through Turkey.

With throughput today at just over 1 bcfd, the line is running effectively at full capacity. The operating consortium has contemplated an expansion, but it would be years off if prosecuted. No incremental volumes coming from Azerbaijan.

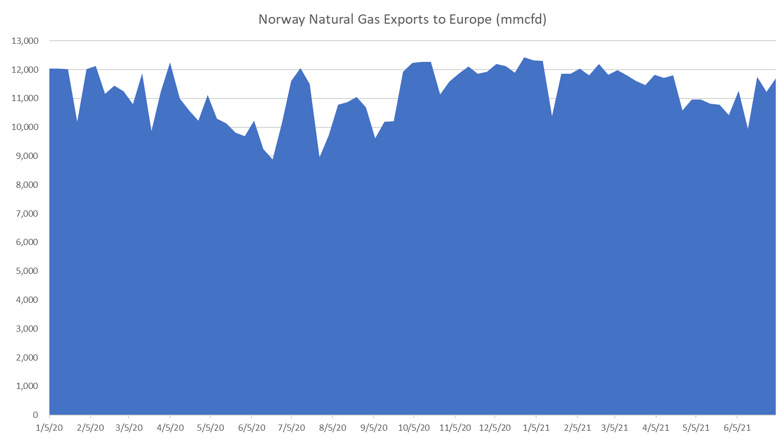

Norway it is then, as the last non-Russian supplier of pipeline gas into continental Europe through pipes running to the UK, Netherlands, France, Belgium, and Germany.

Norway has been a steady supplier since the Ukraine invasion with aggregate volumes near the total export pipeline capacity. The return of Hammerfest LNG later this year, offline some two years after a fire, should be the only material supply addition for the near term. Nameplate capacity of the facility is 600 mmcfd. On the pipes: no incremental volumes coming from Norway.

This of course leaves Russia as the final source of pipeline imports. The chart below, or rather, it’s trajectory of down and to the right, is the genesis of so much consternation in European energy markets. Today, Europe receives 5.3 bcfd of Russian pipeline gas. This time last year, it was 13.7 bcfd.

The purported underlying causes of lower Russian supply are abundant. It started in 2021, when Gazprom reduced spot sales to the continent and chose not to replenish inventories in some of its owned storage facilities. Volumes into CEE plunged. Since then, Gazprom has offered an array of further excuses regarding incremental supply curtailments. We take none at face value, respecting only the continuous downward trend.

In June of this year, flows into Northwest Europe nosedived as well. This time, the rationale was primarily attributed to sanctions-related maintenance issues that were precluding the return of a turbine sent to Canada for repairs. This weekend, reports surfaced suggesting Canada will offer a sanctions waiver permitting the return of the repaired turbine. Bluff called.

Note the blip in July 2021, which shows the downtime related to recurring annual maintenance on the Nordstream 1 line. This same maintenance is slated to occur 7/11-7/21 this year. That is, next week. No one seems to know whether Russia will bring the line back on at all after the maintenance period is complete.

Today, Russia is the only supplier of pipeline gas with the capacity to meaningfully augment deliveries into Europe. And they have been doing the exact opposite for over a year.

LNG

With the loss of Russian pipeline imports and limited upside from other pipeline gas suppliers, Europe has been forced to step up its presence in the global LNG market. Europe does have a reasonably well-established LNG import network with receiving terminals concentrated in northwest Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Iberian peninsula.

Of relevance: the concentration of terminals in Spain/Portugal is effectively meaningless for the rest of Europe. Interconnectivity between Spain and France is limited to ~0.5 bcfd, meaning that the LNG volumes that Spain/Portugal import stay in Spain/Portugal.

Europe LNG Import Terminals

In the pantheon of questionable decisions on European energy policy, the astute reader will find themselves looking at the map above and wondering how it came to pass that the largest consumer and importer of natural gas on the European continent, Germany, has exactly 0 infrastructure to import liquefied natural gas. They’re scrambling now to quickly bring an offshore receiving terminal online by the end of this year – about 10 years late.

LNG import volumes, particularly in northwest Europe, have ramped as Russian pipeline import volumes fell.

Russia pipeline volumes down, LNG volumes up.

Europe was able to pick up the supplemental cargoes in part due to less competition from China earlier this year, who was stuck in rolling lockdowns that curbed LNG demand. We do not extrapolate this trend into 2023.

All the same, Europe’s success in attracting incremental LNG came at a steep price. Throughout the year, Europe’s natural gas price has had to outpace Asia’s to attract the cargoes. This dynamic has seen prices as high as $60/MMBTU.

For reference, European prices in the first half of 2021, before the Russian gas shenanigans began, averaged $7.50/MMBTU. In 2020, they averaged $3.25/MMBTU. Today, it’s $55/MMBTU.

Europe has been able to offset much of the loss of Russia gas with additional LNG imports this year. This pursuit will be more challenging, and more expensive, as we progress through the back half 2022.

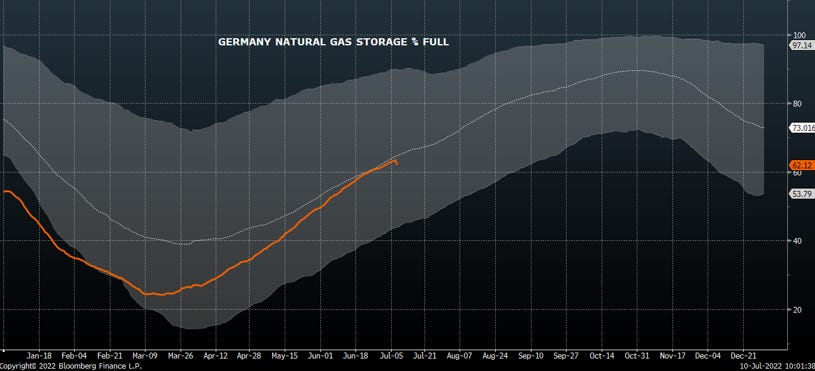

It gets worse from here

Facing ever-increasing risk of further curbs of Russian gas (or even the dire prospect of full cut-off), replenishing gas storage levels before the winter is of paramount importance. Europe in 1H22 did an admirable job in recovering from the storage deficit it suffered, again thanks to Russia, during last winter. At a price, it was able to restock gas inventories and got pretty close to the 5-year average fill level. But last month’s snafu with Gazprom cutting Nordstream 1 flows has proven too much to overcome. Once again, the storage deficit relative to seasonal norms is widening. July’s total shutdown of Nordstream 1 for (at least) 10 days will further exacerbate this trend.

In early July, Germany’s Uniper warned it may need to resort to counterseasonal storage draws to balance supply and demand. The last few days’ data showing an actual drop in inventories is a worrying inflection.

Italy stands well short of seasonal norms, despite access to Azeri gas and LNG imports (boxed out in part by northwest Europe’s scrambling for cargoes).

France, surprisingly, hanging in quite well.

UK, hosting all manner of LNG cargoes it receives to later send back to continental Europe, is sitting pretty.

Having spent the better part of a year trying to outbid Asia for LNG, Europe’s natural gas inventories stand today at 60% full. The end-October target is 90% full.

Maxed out flows from non-Russia pipelines and declining flows from Russia mean Europe will have to be the bid in the global LNG market. It has no choice. Either pay up or have portions of the populace face the very real risk of freezing to death this winter.

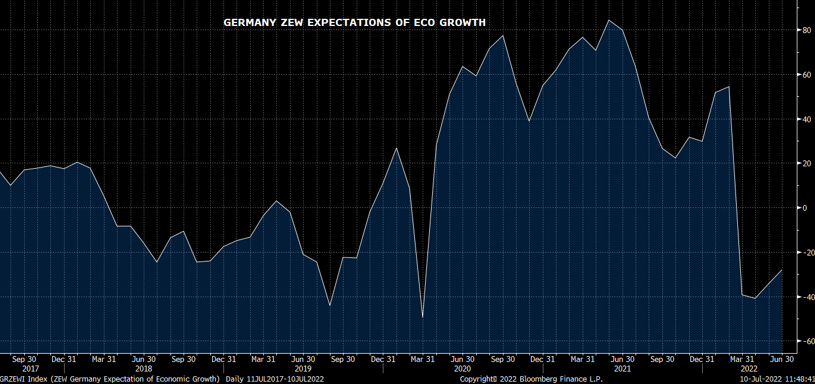

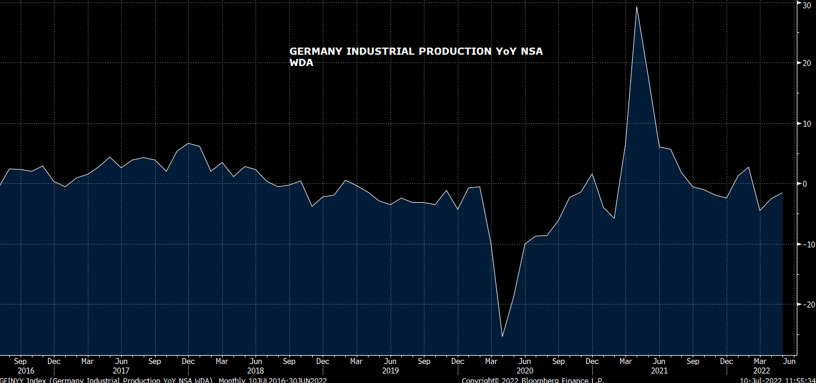

European industry, at a third of continental demand, is already feeling the pain of higher prices. Facilities are turning down or shutting down, economic growth is slowing sharply. Next, residential users will face the same prospect.

Prices have sought to ration demand of course. Stories about adjusting thermostats, taking shorter showers, turning off nighttime street lighting, etc abound.

It’s working to a degree. Demand is down year-on-year. Partly due to a milder spring, partly due to high prices.

Europe is trying to preserve gas supply where it can. Germany is bringing dormant coal-fired power facilities back online to stymie natural gas demand.

But demand today is at the seasonal nadir, the rationing measures are going to help only at the margin. By October, when the weather turns and demand picks up, shorter showers are going to be of little consolation.

High prices have curbed demand, but the impact high prices have not fully flowed to end consumers yet. That part has barely begun. It will get bad this winter and stay bad in 2023.

After seeking a bailout from the state, Germany’s Uniper is seeking for approval to pass through increased fuel costs to consumers.

A similar situation is unfolding in the UK, just as in much the region. We expect this facet of the crisis will rapidly worsen starting in 3Q22.

The big European economies are slowing, before the full effect of higher energy prices has filtered through.

As goes Germany, so goes Europe.

Europe is well past the point of deftly navigating this crisis with minimal economic impact. The tenfold increase in energy prices is inflicting pain across economies, with more to come as the true effect of energy filters through to final consumers.

There are no easy choices. Leaders’ priorities now surely must be not to manage the recession, but to ensure their citizens don’t die this winter. To do this, they’ll pay whatever price necessary to procure enough supply to keep homes heated during the cold months.

Unless they convince Russia to play nice.

This is truly an abysmal situation. There are no winners here. Every plausible outcome visits considerable harm upon a large swathe of people.

Great read--would just urge you to look at storage volume (or days of demand/storage) as well as % full. France and the UK have very little storage relative to their gas consumption, partly because they have reliable LNG inflows, so the % indicator is not as meaningful as the German number.

If Europe is serious about replacing ICE’s with EV’s, coal has to come back in a big way to be able to power all those machines. Two big selling points for coal are it is relatively easy and safe to transport and store on site and it is only exceeded by nuclear in terms of energy density.